For as long as I can remember, hearing stories about my grandpa’s World War II service was part of my childhood. They were my first history lessons outside of school. I spent many weekends and holidays with my grandparents and often heard older relatives bring up his time in the Philippines, Japan, or just talk casually about the war. Hidden at the top of one of grandma’s bookshelves was a thickly bound brown book with large white lettering; ‘WARPATH’, showing a Native American wearing a war chief’s headdress. It was a chronicle of the 345th Bombardment Group and its achievements in the South Pacific. On many occasions, I grabbed it off the shelf and thumbed through the pages looking for grandpa’s face. I knew which unit was his and when I found the respective section, no headshot or group photo. Family lore did say that in one photo taken from behind showing two men rushing out to check on a damaged plane, he was one of them (recognized by his flipped up hat bill, before Gomer Pyle made it fashionable). He very rarely shared some personal war stories and for a long time, all I told others at school or work was he served in the Pacific as a tail gunner in a B-25 bomber over the Philippines.

He passed away in 2006 and that was when I began to learning more. He received medals he never mentioned before and soon there was a cache of old photos and documents filling in the gaps. Since working for the National Archives stirred my history passions and learning about military records, I spent last year and all two months of this year putting together a narrative of his military service. An unexpected miracle happened yesterday when in a vain attempt to find his discharge documents (see the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire) finally paid off. I randomly placed a call to the Garfield County records office in Oklahoma asking if they had any copies. To my surprise they did! Returning WWII veterans normally filed a copy of their discharge documents with the county they returned to in order to receive VA or other government benefits. Thankfully his was still intact and that completed the narrative. My grandpa’s war record here is the best that I have researched with all the available materials. While some information will be lost forever because of the 1973 fire, this is an obstacle facing all military history and genealogy researchers.

Technical Sergeant Fred Laverne Richardson (Service Number 38563209) served in the U.S. Army Air Force from July 20, 1943 to January 14, 1946. Throughout his World War II service, Fred served with the 499th Bombardment Squadron under the 345th Bombardment Group in the V Bomber Command with the 5th Air Force. While overseas, Fred was stationed in Biak, the Philippines, and Ie Shima, participating in aerial combat operations throughout the South Pacific and Sea of Japan. At the end, Fred took part in a handful of major battles in the Pacific Theater of World War II and in the American occupation of Japan. He was twice decorated with the Air Medal for heroic achievements in aerial flight and was later awarded multiple medals for his part in the liberation of the Philippine islands.

Researching World War II-era service records presents a unique challenge because a significant number of records were destroyed in a massive fire in 1973 at the National Personnel Records Center. Approximately 80% of Army records from 1912 to 1960 were affected with varying degrees of damage. Fred’s record was substantially affected by the fire and only a handful of documents survive attesting to his military service. The information given here is extracted from surviving records in Ancestry, Fold3, FamilySearch, Army unit records, local county records, and WWII reference materials.

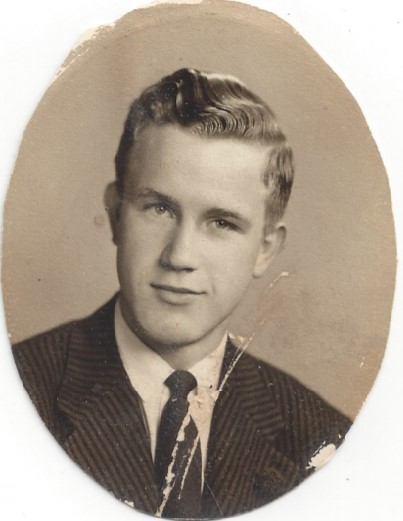

Fred Laverne Richardson was born on April 26, 1925 in Enid Oklahoma to Fred Richardson and Millie Pearl LeGrand. They lived at 508 N. 9th Street and Fred was a senior at Enid High School when he registered for the draft. Local Board #1 in Garfield County recorded his entry the day after his eighteenth birthday on April 26, 1943. Sometime in June 1943, he received a draft notice and was ordered to report to Oklahoma City, where he was formally inducted into the U.S. Army on July 20, 1943. During World War II, inductees were required to serve for the duration of the conflict, plus six months after. This meant that for as long as the war went on, Fred remained in the Army unless he was dishonorably discharged, critically wounded, or killed. Following induction he was transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps and was placed on active duty on August 3, 1943. According to family history, he completed basic training at Amarillo Army Airfield in Amarillo, Texas. Aerial defense, air artillery, and forward observing courses were taught at Amarillo AAF and if Fred was later assigned to an Army Air Force unit, he would have received physical and aerial warfare training there. The airfield trained recruits on B-17 Flying Fortresses; four engine long range bombers capable of flying hundreds of miles and dropping thousands of pounds of bombs individually.

Aerial combat training was tremendously harsh and a small percentage completed the physical battery. Those who passed went onto flight education and armament training. Fred’s recently discovered Notice of Separation (discharge summary) shows he attended two service schools: Aircraft Armament Training School at Lowry Field, Colorado, and Aerial Gunnery Training School at Fort Meyer, Florida. One family story is that his aerial gunner training consisted of shooting skeets with shotguns out the back of a moving truck. Service schools offered specialized training for enlisted personnel. Enlisted men did not serve as pilots, navigators, or bombardiers. Commissioned officers served these roles.

Fred completed all training by approximately July 1944. From family photographs taken before shipping out, he received his assignment to the U.S Army Air Force and was promoted to the rank of Corporal. This is shown by the chevrons on the sleeve and shoulder patch. The separation document lists his military occupational speciality as Airplane Armorer Gunner. The job duties included inspecting, repairing, and maintaining all aircraft armament, including bomb release mechanisms, airplane cannons, machine guns, and auxiliary equipment. He made daily inspections and repaired equipment such as bomb racks, bomb release mechanisms, aerial gun sights, flare racks, and chemical carrying release mechanisms. He also installed armament equipment on airplanes, and placed bombs in bomb racks. The last portion was to man a machine gun position if combat occurs during flight.

Family history states that Fred was originally ordered to report to the European theater and while in New York, his orders changed and was transferred to the 345th Bomb Group. Fred traveled to Camp Stoneman near San Francisco, California. This was a staging area for servicemen joining their units in the Pacific. On October 17, 1944, Cpl. Fred Richardson departed the United States. By the autumn of 1944, the U.S. had pushed the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy out of the southern Pacific and began prepping for the liberation of the Philippines. The country had been under Japanese occupation since May 1942 after the Battle of Bataan. Invasion plans had been in the works since 1943, but the outlying territories needed to be retaken first.

History of the 345th Bombardment Group

Air warfare changed drastically since the First World War. Technological innovations created larger and faster planes with increased carrying capacity. Long and medium range bombers were capable of dealing out tremendous damage. The new B-25 Mitchell debuted in 1941 and the Army Air Force was eager to use it in combat. It was a medium range bomber equipped with twelve .50 caliber machine guns, a 75mm cannon, and could carry up to 3,000 pounds of bombs and incendiaries. Each plane carries five crew members; pilot, navigator / bombardier, gunner / engineer, radio operator / waist gunner, and tail gunner. On November 11, 1942 the 345th Bombardment Group was activated under the 3rd Air Force and trained until April 1943 when they moved to Camp Stoneman and entered combat in New Guinea in June 1943 where it became part of the 5th Air Force. The group comprised of four squadrons:

From Left to Right: 498th Bomb Squadron ‘Falcons’, 499th Bomb Squadron ‘Bats Outta Hell’, 500th Bomb Squadron ‘Rough Raiders’, 501st Bomb Squadron ‘Black Panthers’

The unit was intended for service in the European Theater of Operations, but U.S. Army General George Kenney specifically requested them to redeploy to the south Pacific following successful bombing campaigns near Australia. New Guinea and the Bismarck Islands were the first stage of the 345th’s campaign. Their actions performing reconnaissance missions, dropping supplies, and attacking Japanese ships through the Bismarck Sea arguably prevented a serious threat to Australia. Between April 1943 and July 1944, the 345th relentlessly attacked the Japanese garrisons and ships running through the sea. The triple approach of high level bombing, heavy machine gun strafing, and skip-bombing (bouncing the bomb off the water similar to skipping a stone across a pond) was effective in breaking Japanese control and opening the way for the liberation of the Philippines.

They took to the skies again from July to November of 1944 hitting targets in the southern Philippines. Biak was the next step in the unit’s path and after taking the island, could run missions over the Celebes Sea. The Japanese knew that the United States would reclaim the country and the 345th made it a point to cut a path to Luzon and clear the war for the American recapture. Mission after mission, the 345th lost hundreds of crews and bombers as they were shot down by Japanese fighter planes or hit by flak from enemy ships. During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, a kamikaze hit a group of 345th personnel stationed on the ground before they could get airborne. By the beginning of 1945, the 345th began bombing missions as far north as the Sea of Japan, hitting shipping and communication lines down through China and southeast Asia. Destroying such targets were necessary for military planners as operations were drawn up for the long anticipated invasion of the Japanese home islands (Operation Downfall). Both the United States and Japan knew that the cost in human lives would be astronomical. Intelligence analysts at the time estimated that casualty figures would easily reach into the millions as the Japanese military and civil defense organizations prepared for invasion.

By July 1945, the 345th was positioned on Ie Shima in the Okinawa island chain ready to receive new combat orders. On August 6th and 9th when Hiroshima and Nagasaki were hit with the first atomic bombs. Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender six days later on August 15th and now the 345th had a different set of orders: to escort the Japanese emissaries for the formal surrender before General MacArthur. Three B-25s and fighter planes were ordered to escort the Japanese detachment to the Philippines where they began discussing the terms of surrender and allied occupation of Japan. The escort was not without some hiccups though; hard-line nationalists in the Japanese military wanted the escort shot down because tradition held that surrender was worse than death. These fears were assuaged as the 345th escort mission formed a bracket around the Japanese planes and chaperoned them safely to Manila. Surviving airmen of the 345th remained stationed on Ie Shima until they received orders to rotate back to the United States and on December 29, 1945, the unit was deactivated.

Throughout the Pacific campaign, the 499th squadron carried out its own specific missions. Fred left the U.S. on October 17, 1944 and arrived in the Pacific theater on November 23, 1944. The 499th conducted operations between Biak and the Philippines attacking Japanese shipping convoys and battleships. Between December 1944 and July 1945, Fred and his squadron flew from San Marcelino and Clark Air Fields hitting targets all over the Philippines. The longest range mission that they ever carried out was an attack on Saigon in southern Vietnam in April 1945. It was by far the most dangerous mission they ever undertook, but it earned them a Distinguished Unit Citation.

While in Ie Shima, Fred became part of the occupation force following Japan’s surrender. An old family photo album containing pictures from WWII includes some unique ones; photos of the Japanese surrender delegation. The images are quite small, but when seen through a magnifying glass, one can see the Japanese wearing traditional garments and presenting instruments of surrender. Unfortunately there are no captions on the reverse side of the pictures making it hard to determine when or where the photo was taken, but from judging the content, many pictures were taken in the Philippines and Ie Shima. Cultural landmarks and buildings place some early pictures in Manila. Fred took a lot of pictures of local people and he even collected a large amount of foreign currency and Army scrip.

Between Fred Richardson’s personal achievements and assignment with the 499th Bombardment Squadron and 345th Bomb Group, he received a substantial number of awards, both U.S. and foreign awards. The following are the most complete listing of awards he is entitled to from World War II.

Aerial Gunner Badge: this military aeronautical badge was given to those who qualified and endured hazardous conditions as an aerial gunner. A winged bullet fixed on the standard observers badge, Fred received this badge for his military occupational specialty as an Airplane Armorer Gunner a B-25 bomber.

Air Medal: Established in Executive Order 9158, the Air Medal recognizes acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight. Flight conditions, combat missions, and the number of sorties were taken into account when determining who received the Air Medal. Between October 1944 and December 1945, Fred received the Air Medal twice, giving him an Oak Leaf Cluster. Both awards were issued by a General Order from 5th Air Force HQ for meritorious service with the 345th Bomb Group.

Good Conduct Medal: The Good Conduct Medal recognizes servicemen who served honorably for a specific amount of time. Criteria for the Army Good Conduct Medal has changed via executive orders in subsequent presidencies. The medal was also established during World War II and each service branch has its own version. The medal can also be awarded to any servicemen who completes at least one year of honorable service while the United States is at war. Fred met this criteria and received the Good Conduct Medal.

American Campaign Medal: Established in Executive Order 9265, the American Campaign Medal is awarded to all service members who were stationed in the American Theater of Operations (ATO). This includes the continental American territory and the surrounding waters of both North and South America. Servicemembers must have served at least one year within the continental limits of the U.S., 30 days outside the continental U.S. within the ATO, or 60 days onboard a vessel in American waters. Having served at least one year within the continental limits of the U.S. while stationed at Fort Sill, Fred received the American Campaign Medal.

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal: Established in Executive Order 9265 along with the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal is awarded to all service members who performed military duties in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater (APT). This includes air, naval, and ground operations. Service stars denote participation in a campaign. Because air operations were ongoing from the beginning to the end of the war (with the exception of some isolated campaigns) Fred received service stars for the following campaigns:

Air Offensive, Japan (5 June 1943 – 2 September 1945)

China Defensive (5 June 1943 – 4 May 1945)

New Guinea (5 June 1943 – 31 December 1944)

Bismarck Archipelago (15 December 1943 – 27 November 1944)

Leyte (17 October 1944 – 1 July 1945)

Luzon (15 December 1944 – 4 July 1945)

Western Pacific (17 April 1945 – 2 September 1945)

China Offensive (5 May 1945 – 2 September 1945)

World War II Victory Medal: Created by an Act of Congress on July 6 1945, this service medal recognizes all personnel who served in the U.S. Armed Forces from December 7 1941 to December 31 1946. No minimum time in service is needed to award the World War II Victory Medal. Over 12 million service members are eligible for the award, making it the second-most awarded medal in the U.S.; the most being the National Defense Service Medal created in 1953. Having served in World War II, Fred automatically received the subsequent victory medal.

Army of Occupation Medal: Established by the War Department in 1946, the AOM recognizes personnel who participated in any duties in occupied countries following the cessation of hostilities in both Germany and Japan. At first the medal was only for ground forces, but it was later amended in 1948 to include any Army Air Force units. The medal has an accompanying clasp for where the service member was stationed. The 345th Bomb Group served for six months on the island of Ie Shima, technically considered occupied enemy territory. This entitles Fred the Army of Occupation Medal with the ‘Japan’ clasp.

Philippine Liberation Medal: The liberation of the Philippines was a major moment during the war in the Pacific. They were the first major U.S. possession to fall to the Japanese and thousands suffered as POWs. In commemoration of those who took part in the campaign, the Philippine government created the Philippine Liberation Medal. Initially only a ribbon, a medal was created later in July 1945. The PLM also included service stars similar to the APCM. Stars were awarded for the following criteria:

- Participation in the initial landing operation of Leyte and adjoining islands from 17 October to 20 October 1944.

- Participation in any engagement against hostile Japanese forces on Leyte and adjoining islands during the Philippine Liberation Campaign of 17 October 1944, to 2 September 1945.

- Participation in any engagement against hostile Japanese forces on islands other than those mentioned above during the Philippine Liberation Campaign of 17 October 1944, to 2 September 1945.

- Served in the Philippine Islands or on ships in Philippine waters for not less than 30 days during the period.

The 345th did not participate in the initial landing operation on Leyte on October 17-20 (Fred was also en route to Biak from Camp Stoneman). Fred does meet the other three criteria so he received three service stars on the PLM.

Philippine Independence Medal: After the Japanese surrender, the Philippine government wanted to recognize all those who served in both the initial defense of the nation and the subsequent liberation. The Philippine Independence Medal was created to recognize those who took part in either one of the conflict stages. Because Fred took part in the liberation campaign, he received the PIM.

Presidential Unit Citation: President Franklin Roosevelt created this unit citation, (originally entitled the Distinguished Unit Citation) via Executive Order 9075. A unit citation was a new type of award for the U.S. military; it was meant to recognize the gallantry and heroism of a unit that endured dangerous conditions. The 499th received three PUCs for its entire wartime service; Fred served with the squadron when it received its third citation and his only one for actions over Indochina.

Philippine Presidential Unit Citation: Similar to the U.S. Presidential Unit Citation, the PPUC was awarded by the Philippine government to recognize the meritorious service and heroic achievements to those who participated in any Philippine operations. Because Fred served with the 499th which operated in the Philippines, he received the PPUC.

All U.S. Army, Army Air Force, Navy, and Marine personnel who were honorably discharged also receive the Honorable Service Lapel Button, nicknamed the ‘Ruptured Duck’. This was given to all those that were honorably discharged during World War II. The award had a twofold purpose: to show proof of military service while wearing civilian clothing [the lapel button was not worn with military uniform] and to receive recognition from agencies and private companies that the wearer was a veteran and could receive benefits such as reduced fares or free services. Since Fred completed his service honorably, he received the Ruptured Duck. A diamond shaped cloth patch was also issued for a veteran that could be worn on their Class A uniform for a subsequent 30 days.

Fred’s separation document (discovered February 18, 2021) shows that he also received a weapons marksmanship badge. Recruits are tested on their weapons proficiency during basic training and are scored on accuracy, technical skills, and speed. There are three categories of badges; Marksman, Sharpshooter, and Expert. Individual weapons bars are attached on each badge denoting the level of proficiency with that weapon. Fred was awarded the Sharpshooter badge with the Carbine bar on October 7, 1943.

Fred returned to the U.S on January 3, 1946 and was sent to Fort Leavenworth for separation. The Army was demobilizing thousands of troops a week, sending them to various locations across the country to expedite the process. On January 14, 1946, Fred was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army Air Force. His wartime service was over. He served for two years, five months, and twenty-five days; a year and two months of which was overseas.

According to family oral history, he completed forty-two missions with the 499th and made it out physically unscathed. The path he traveled took him across the United States, the entire width of the Pacific Ocean, and to foreign countries that a regular kid from Oklahoma might never have seen in his lifetime. Seven months after his discharge, he married Roberta Davis on August 18, 1946 and began a career with the Frisco Railroad. On 25 June 2006, Fred Laverne Richardson died from natural causes at the age of eighty-one. Four years later, Roberta joined him; together they both completed ‘well-finished lives.’

The 5th Air Force and my father’s 11th Airborne Division had close ties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read a lot about the 11th Airborne. That was quite an outfit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was amazed when I really got into the research!!

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s awesome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is super cool! It’s amazing that you were able to find his separation document after all this time. Thanks for sharing your passion.

LikeLiked by 1 person